한국어 번역 - 클릭 Italiano Français Español

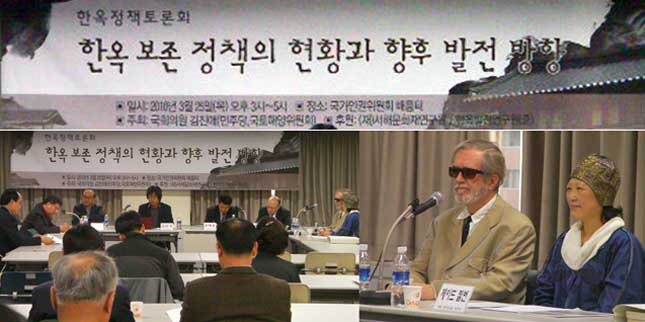

A talk on March 25th 2010, at the National Human Rights Committee Study Centre, Seoul

한국어 번역 - 클릭

Italiano Français Español

![]()

Photos by Sandy Soh |

I think it is very significant that this meeting is taking place in a building concerned with Human Rights.

The development of modern ideas about the protection of heritage is connected with thinking about human rights. I will explore this a little later in my talk.

However, last month, I noticed a news article about how the Seoul plans to develop measures to protect the city’s cultural heritage within the four great gates. News about the protection of heritage is always good – heritage has enormous social, cultural, and economic values.

Let me clarify what I mean by the word “heritage”

The word heritage once referred just to a country’s major works of art and architecture. It covered the monuments, palaces, castles, cathedrals and other major buildings that survived from past generations to the modern world.

However, since the 1950s the concept of cultural heritage has broadened from historic monuments and major works of art. It now includes the natural landscape, gardens, towns, villages, and ordinary houses. Intangible heritage, such as the traditional skills of craftsmen and performing artists are also now recognised as a vital part of each country’s heritage. UNESCO, the Council of Europe, and other major international bodies all recognize this broader definition of “heritage.”

The Venice Charter of 1964 was the first of a number of international agreements expressing these ideas. Successive agreements have built on these foundations, providing not only a moral and philosophical background to the need for conservation but also the means to obtain practical advice, and international support.

Heritage is valued because it is a vital part of each country’s DNA. In a world that increasingly promotes globalisation and global standards, Heritage represents cultural diversity. It forms part of each nation’s sense of identity and the unique values each has evolved over the centuries.

More important than the announcements about heritage protection, however, is what is done to protect, heritage, and solve the problems that may arise in doing so.

For this reason, I would like to begin by exploring what has been happening in Bukchon over the last eight years.

Bukchon, the district between the Gyeongbok and the Changgyeonggung was the heart of the old city of Seoul, and this is where my mother-in-law, my wife, and I have lived since 1988, in Kahoi-dong 31. Until recently, Kahoidong 31 was the very last district in Seoul where you could see a few complete streets of original hanoks, looking as they did almost 100 years ago.

Since 1976, the Seoul Government has claimed it has policies to preserve the hanoks of Bukchon. Yet the simple fact is that the government repeatedly sanctions exceptions to its policies. The result is a continuing decline in the number of hanoks.

When we first went to live in Kahoidong in 1988, there were about 1,500 hanoks in Bukchon. Today there are only about 900, and the number keeps falling.

Only a week ago, another hanok in our own street in Kahoi-dong was demolished. Ours is now the only original building left.

Some more examples:

For example, the whole of Kahoi-dong 1 district was demolished to allow the Hanwha Group to build luxury villas. This single project erased 88 hanoks.

In addition, as part of the Bukchon Restoration Plan, most of the hanoks in my own part of Kahoi-dong - Kahoi-dong 31 – have been demolished and replaced by two storey modern concrete buildings with hanok-style roofs.

Kahoi-Dong 31 is graded as an S1 Preservation Area and, according to government reports, had the highest concentration of original hanoks in the whole of Bukchon, nearly all in good or excellent condition.

The Bukchon Plan changed all that. Some hanoks were demolished illegally. Many owners were given grants for restoration of existing hanoks and allowed to use the money for demolition. Some residents were forced to sell their hanoks by intimidation. Moreover, some hanoks were deliberately damaged to make the case for demolition. City authorities, the police, the prosecutors, the courts all declined to take any action when confronted with evidence of these abuses.

Seoul City also permitted the demolition of traditional hanoks it had already given an S1 status. In their place, it approved the erection of new concrete buildings, which included traditional roofs.

There is a depressing similarity to events at Yongsan and Yong Gang, where Seoul city also failed to respect and protect the rights of citizens. We must ask what is the powerful force that motivates public officials to ignore their basic duty of serving society and upholding both the law and people’s rights.

Many of the new buildings violate Korea’s basic construction laws – they differ substantially from approved plans. Notably, they are taller than permitted. The Seoul government ignores all of these issues.

While it is perfectly OK to erect new buildings that mix traditional and modern styles, I feel it is not acceptable to demolish the last few authentic hanoks to do this. There are many areas in Bukchon where indiscriminate development in the past has created out-of-character buildings and which might benefit from new thinking.

No matter how you count the figures, the number of hanoks in Bukchon today is at least 40% less than in 1985.

The Seoul Metropolitan Government is directly responsible for this reduction in hanok numbers during a period in which they claim to have had preservation policies! On the government’s own figures, their policies have been a total failure.

Although the Seoul government used the language of protection and conservation, to describe what they were doing in Bukchon, the implementation of the plan was almost a typical urban redevelopment project. Old buildings were bulldozed to make way for modern new buildings.

I say “almost” because there is a difference. The changes, the demolitions, in Bukchon were all financed with taxpayers’ money. The grants for demolition were paid from public funds, and subsidized new owners for whom a Kahoidong home was often their second or third residence.

What was once a lively local community of long-term residents is now a ghost town owned by land speculators.

Achieving goals of heritage protection is not always easy. It is also an international issue, involving UNESCO and many other global, regional, and national organisations. My own experience comes originally from the UK and Europe where these are important questions.

There are laws and regulations, both at a national and a local level to protect the country’s heritage. There are also both national and local organisations with responsibilities for heritage protection.

The government has wide powers to register buildings, open spaces of land as heritage assets because they have special historic, archaeological, architectural, artistic, or cultural interest. Additionally, any individual can apply to the government requesting that a building, district, or open space should be declared a heritage asset.

When a building is registered, any work done to it requires prior approval. There may also restrictions on buildings that are adjacent to make sure that any work done to these does not affect the listed building.

The building owner also has a duty to care for the building and to keep it in good repair. There may be controls over the materials and techniques used in repairs to ensure that the authentic character of the building is retained. The government also has the right to enter a building and inspect it to ensure that it is being properly maintained and to examine any repairs and alterations.

If an owner neglects these duties, the government can require him to carry out repairs or take over the ownership. The owner might also receive a jail sentence of up to two years and be required to pay a fine of up to £20,000 (about KRW 35 million). These are serious penalties. In contrast, the fine for illegally demolishing a hanok in Seoul is only KRW 300,000.

Of course, maintaining or repairing an old building may be difficult and expensive, but there are grants and professional advice available to help with this.

Sometimes large areas comprising many buildings that may not warrant individual registration but are still considered as heritage are given the looser protection of designation as a conservation area.

Currently, about 500,000 individual buildings have registered status and if we include conservation areas and buildings adjacent to registered buildings, approaching 1 million old buildings have at least some degree of protection in the UK. These include all buildings erected before 1700 and most of those erected before 1945.

In the UK, great attention is given to authenticity. In restoration and preservation work, it is considered important to use the original kinds of materials and craftsmen techniques as far as possible. This is also considered “best practice” throughout Europe. Sadly, this idea is missing in Seoul City’s projects that maximize the use of ready-mix concrete and unskilled labour.

In the UK, there are both national and local organisations involved in heritage.

The largest is a charity, The National Trust, founded in 1895. The National Trust is now the largest private landowner in the UK, and the largest conservation organisation in Europe. It is owned by its 3.6 million members (that is about 6% of the UK population), ordinary people who pay an annual subscription fee.

The National Trust is completely independent of business or the government. It earns its revenue not only from membership fees but also from donations, admission fees, and the sale of books, films, and other materials to do with England’s heritage. It is also supported by the volunteer efforts of 55,000 people who work for it part-time and without payment.

There are National Trust organisations in about 15 countries now (e.g. Japan, USA, Australia, Bermuda, Ireland, etc) but none of these has yet achieved the same degree of popular support, reputation, or influence as that in the UK.

Although the National Trust is now mainly associated with the preservation of buildings and the countryside, that is not how it began in 1895.

At its foundation, the National Trust was a human rights organisation.

In the 19C, enormous social changes were taking place in the UK. There were new technologies based on coal and steam, and new industries. Cities grew rapidly to provide the labour for new factories, and there was massive population growth. England was changing from a stable, traditional agricultural society to a modern industrial one.

Against this background, wealthy landowners saw an opportunity to take complete control of large areas of countryside and common land where ordinary people were traditionally free to grow crops, keep animals, cut firewood, and pursue many other traditional occupations.

The rights ordinary people held to use the land often went back over 1,000 years. The landowners, many of whom were members of parliament, began to pass new laws allowing them to fence the land off from ordinary people and use it exclusively for their own money-making purposes. These changes led to considerable social unrest.

The three founders of the National Trust were concerned by both the changes in land use and attempts to remove the traditional rights of ordinary people.

One of the three founders, Robert Hunter, was a lawyer who devoted his time to finding legal ways to protect the rights of ordinary people. Both through courts and the essays he wrote, his work had enormous influence and obliged government to rethink what was acceptable to society. This work led him to become one of the founders of the National Trust.

Today, there are still about 1.3 million acres (5,261 square km, or 1,591,322,852 pyong) of common land in England and Wales, about 3.5% of the total land area. This is largely a result of the work of Robert Hunter and the National Trust. If you visit London, Hampstead Heath is one example of “common land.”

The second major national body, English Heritage, is a government organisation and the Government's statutory adviser on the historic environment. It plays a major role in the development of policy, legislation, education, and promotion. It also owns or manages many properties. English Heritage was established in 1984, but government involvement in heritage protection goes back to 1892.

In addition to the work of these major bodies, many historic buildings and districts are owned or managed by preservation trusts that depend on the willingness of thousands of people to contribute their time and resources to preserve a part of the country’s heritage. In London, Hampstead Garden Suburb is one example. Another example: the older parts of Letchworth, a town near London, are managed by a Heritage Foundation. Both were built early in the 20C.

Heritage protection is successful in the UK partly because of the existence and enforcement of laws and regulations. However, the laws have followed on from the work of private individuals. Fundamentally, the success reflects the simple fact that ordinary people in the UK value their heritage and think it is very important to preserve it.

In a survey in England, 96% of people thought that the historic environment was important to teach young people about the past; 88% thought it was important in creating jobs and boosting the economy; 87% thought it was right to use public money for preservation; 87% also thought it plays an important part in the cultural life of the country. These ideas were supported across all age groups, and especially by young people.

The economic values of heritage are enormous. In the UK, the heritage-based visitor economy is currently worth £20.6 billion (KRW 36 Trillion), supporting 466,000 UK jobs. Every £1million (KRW 1,702 million) of heritage funding leads to an increase in tourism revenues of £4.2million (KRW 7,512 million) spread over 10 years. This more than justifies the cost of heritage protection

Taking the UK figures as a yardstick would suggest that Korea could be capable adding at least KRW 27 Trillion and over 300,000 jobs to its economy through the protection of heritage assets, all on a long-term basis.

The destruction of heritage in Bukchon has only benefitted a small number of wealthy individuals and speculators. Heritage protection would have benefitted the whole of society for a very long period.

Heritage is a key draw for foreign visitors: In 2009, 30% of them cited it as a main reason for travelling to Britain, compared with 27% for business, and 15% visiting friends and family.

Heritage is a concept that generally evokes positive ideas. This includes the preservation of our material culture – the objects that we see and use every day, that our parents and previous generations have valued and used, and of course the unspoiled natural landscape. It also includes intangible culture – performances of dance, song, music, theatre, performing arts, religious and social rituals. All these are generally regarded as something we all share, and which benefit us not only individually but also as a community. It is through our interactions with this shared heritage and with each other that we build not only our own identities as human beings, but also but also the identity of our family, our community, and our country.

For these reasons, many people now consider that access to heritage is a basic human right, and this is reflected in recent UN declarations.

I think there are some special reasons why heritage protection is very difficult in Korea. The events of the 20C – the Japanese occupation that tried to eradicate Korean culture, the Korean War, the division of the country, and the period of military rule – were traumatic. These events broke many of the natural links between the Korean people and their cultural heritage, and we can now see the terrible consequences.

South Korea is an urbanised, sophisticated, wired society. According to the Financial Times, per capita income in purchasing-power terms is about $28,000 - only $5,000 behind archrival Japan. South Korea’s economy is practically as big as India's but with a population less than one-twentieth the size. It exports more goods than the UK.

In the 1960s, South Korea had a per capita income on a par with sub-Saharan Africa yet it is now snapping at the heels of Britain and France. Indeed, South Korea has progressed too far to continue pretending it is an economic underdog.

Government officials talk of their wish for Korea to become an advanced nation.

In terms of manufacturing and technology, it has already achieved this status. However, this is not enough to qualify as an advanced nation. The rule of law, respect for human rights, protection of cultural heritage, are all part of being an advanced country. In these areas, it is regrettable that Korea has made much less progress over the past 50 years.

Surely, it is time now for South Korea to claim its rightful place among the advanced nations by raising its respect for the rule of law, for human rights, and the protection of its unique cultural heritage to the level of other advanced nations. Human rights and heritage are inseparable.

These topics are far too important to leave to government or the courts to decide. They require the vigorous, active involvement of ordinary people, because that is how democracy works in an advanced society.

Thank you for listening.

David Kilburn

![]()